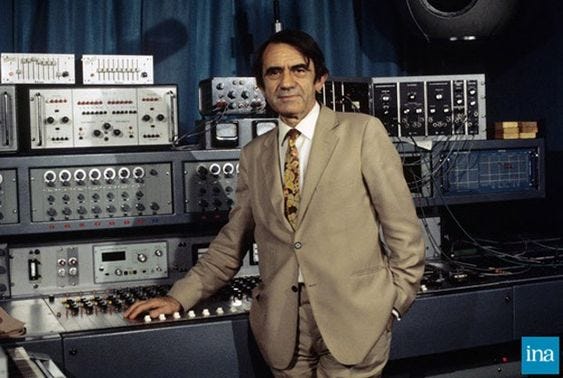

Pierre Schaeffer’s Sound Revolution: A Journey into Musique Concrète

In the beginning there was no musical notation, there was no time signature and there was no sound recording. In the beginning there was only pure unadulterated sound. Cavemen would bang rocks and sticks together, and when some combination of these items produced a sound they liked they would return to it again and again. Over time more sophisticated in…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Beautiful Monsters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.